WHO WROTE LAMENTATIONS?

While the author of Lamentations remains nameless within the book, strong evidence from both inside and outside the text points to the prophet Jeremiah as the author. Both Jewish and Christian tradition ascribe authorship to Jeremiah, and the Septuagint—the Greek translation of the Old Testament—even adds a note asserting Jeremiah as the writer of the book. In addition, when the early Christian church father Jerome translated the Bible into Latin, he added a note claiming Jeremiah as the author of Lamentations.

The original name of the book in Hebrew, ekah, can be translated “Alas!” or “How,” giving the sense of weeping or lamenting over some sad event.1 Later readers and translators substituted in the title “Lamentations” because of its clearer and more evocative meaning. It's this idea of lamenting that, for many, links Jeremiah to the book. Not only does the author of the book witness the results of the recent destruction of Jerusalem, he seems to have witnessed the invasion itself (Lamentations 1:13–15). Jeremiah was present for both events.

WHERE ARE WE?

“How lonely sits the city / That was full of people!” (Lamentations 1:1), so goes the beginning of Lamentations. The city in question was none other than Jerusalem. Jeremiah walked through the streets and alleys of the Holy City and saw nothing but pain, suffering, and destruction in the wake of the Babylonian invasion of 586 BC. It also makes sense to date the book as close to the invasion as possible, meaning late 586 BC or early 585 BC, due to the raw emotion Jeremiah expresses throughout its pages.

WHY IS LAMENTATIONS SO IMPORTANT?

Like the book of Job, Lamentations pictures a man of God puzzling over the results of evil and suffering in the world. However, while Job dealt with unexplained evil, Jeremiah lamented a tragedy entirely of Jerusalem's making. The people of this once great city experienced the judgment of the holy God, and the results were devastating. But at the heart of this book, at the centre of this lament over the effects of sin in the world, sit a few verses devoted to hope in the Lord (Lamentations 3:22–25). This statement of faith standing strong in the midst of the surrounding darkness shines as a beacon to all those suffering under the consequences of their own sin and disobedience.

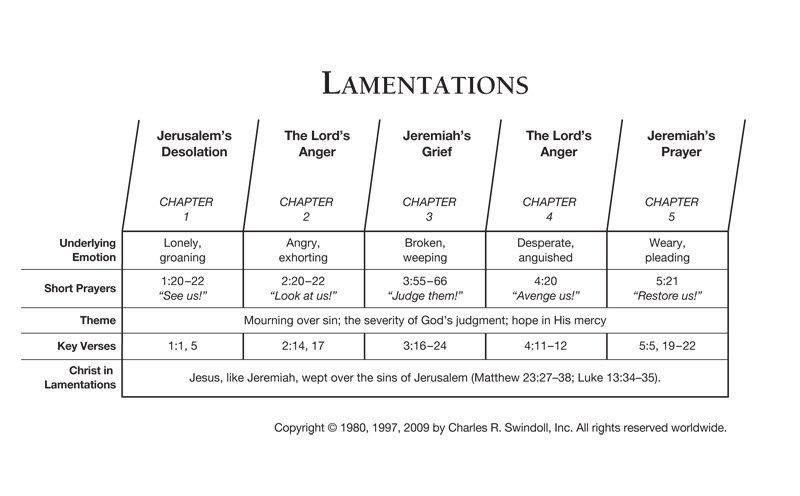

WHAT'S THE BIG IDEA IN LAMENTATIONS?

As the verses of Lamentations accumulate, readers cannot help but wonder how many different ways Jeremiah could describe the desolation of the once proud city of Jerusalem. Children begged food from their mothers (Lamentations 2:12), young men and women were cut down by swords (2:21), and formerly compassionate mothers used their children for food (4:10). Even the city's roads mourned over its condition (1:4)! Jeremiah could not help but acknowledge the abject state of this city, piled with rubble.

The pain so evident in Jeremiah's reaction to this devastation clearly communicates the significance of the terrible condition in Jerusalem. Speaking in the first person, Jeremiah pictured himself captured in a besieged city, without anyone to hear his prayers, and as a target for the arrows of the enemy (3:7–8, 12). Yet even in this seemingly hopeless situation, he somehow found hope in the Lord (3:21–24).

HOW DO I APPLY THIS?

Lamentations reminds us of the importance not only of mourning over our sin but of asking the Lord for His forgiveness when we fail Him. Much of Jeremiah's poetry concerns itself with the fallen bricks and cracking mortar of the overrun city. Do you see any of that destroyed city in your own life? Are you mourning over the sin that's brought you to this point? Do you feel overrun by an alien power; are you in need of some hope from the Lord? Turn to Lamentations 3:17–26, where you'll find someone aware of sin's consequences and saddened by the results but who has placed his hope and his trust in the Lord.

End Notes

1. Charles H. Dyer, "Lamentations," in The Bible Knowledge Commentary: Old Testament, ed. John F. Walvoord and Roy B. Zuck (Wheaton, Ill.: Victor Books, 1985), 1207.